The Iu Mien can be found in Southern China, the northern provinces of Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Western nations such as the United States, Canada, and France. In recent years, small Iu Mien communities have also emerged in Australia and other parts of East and Southeast Asia, largely due to emigration from Laos and Thailand. Across these diverse locations, the Iu Mien have largely assimilated into the local populations, making it challenging to associate them with any single nation-state.

The terminology used to refer to the Iu Mien reflects the complexity of their identity. When discussing the Iu Mien as a subgroup of the broader Yao nationality in China, the term “Yao” is commonly used as an umbrella term encompassing all subgroups. This classification extends to Vietnam, where the Yao are officially recognized as the Dao. Within their own communities, however, the Iu Mien refer to themselves as “Iu Mien” or simply “Mien.”

Beginning in the 1950s, the Chinese communist government initiated an “ethnic classification” project aimed at formally recognizing China’s numerous nationality groups. Research teams were deployed to study shared territorial zones, language, cultural practices, and other identifying factors. By the project’s conclusion, the Yao (or Yaozu) were officially classified as one of China’s fifty-four nationalities, a number that later increased to fifty-five with the addition of the Jino in 1974. Today, the Yao are primarily concentrated in the mountainous regions of Hunan, Guangxi, Guangdong, Guizhou, and Yunnan provinces, with a population of approximately 2.63 million.

The Iu Mien are a subgroup of the Pan Yao branch, one of the three major Yao groups identified by the Nationalities Affairs Commission of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, along with the Bunu Yao and Pingdi Yao. Yao languages are generally classified within the Miao-Yao (Hmong-Mienic) branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, though there is ongoing debate among linguists regarding this classification. Some argue that Miao-Yao constitutes a distinct language family, separate from the Sino-Tibetan group. Despite differences in dialect, traditional attire, and cultural practices, Yao subgroups share several key characteristics.

Jeffrey L. MacDonald, in his anthropological research on the Yao, identifies four areas of commonality among Yao subgroups. First, many Yao believe they are descendants of the mythical figure Panhu (King Pan), a dragon-dog warrior who, as a reward for his service to a Chinese emperor, was given a wife, land, and the title of king. Their descendants are considered the twelve original clans of the Yao. Additionally, Yao subgroups have historically practiced Yao Daoism, a syncretic form of ritual Daoism that blends native animist beliefs with Chinese Daoism. The Yao are also unique among upland peoples for adapting the Chinese writing system, primarily for religious purposes. Lastly, Yao leaders historically adhered to the legitimacy of the “Crossing the Mountain Passport” (Jiex Sen Borngv), an imperial decree that granted them specific privileges, including the right to freely roam the mountains and seek arable land.

Ancient Chinese records regarding the Yao, though inconsistent, generally suggest that tribes in the region now known as northern Hunan province shared a common ancestry. Before the Qin Dynasty (221 BCE), Southern China included regions beyond the Han Chinese core, inhabited by various tribal groups. Chinese states often grouped these tribes based on geographic networks, using broad terms such as “Man” (barbarians) and “Nanman” (southern barbarians). Variations of “Yao,” including “Moyao,” “Yaoren,” and “Manyao,” were not exclusive to a single ethnic group. It is widely accepted, however, that some indigenous groups in ancient China’s Dongting Lake region of Hunan province are ancestors of today’s Yao.

Throughout much of Chinese history, the Yao experienced alternating periods of peace and tension with the Chinese state. Historically, the Yao lived in lowland areas but were pushed into the mountains due to Han Chinese migrations. Their relationship with the state was managed through a “loose reins” policy, which allowed for varying degrees of autonomy. During Han migrations, many Yao chose to retreat into less controlled mountainous regions, establishing a way of life centered around slash-and-burn agriculture. This practice, however, was unsustainable, necessitating frequent relocation.

The Yao traditionally practiced a medieval form of Daoism, known as Yao Daoism, which they adapted, along with the Chinese writing system, during the 12th or 13th centuries. Yao Daoism represents a synthesis of Chinese Daoism, indigenous animistic beliefs, and ancestor worship. This traditional religion has profoundly influenced Yao social dynamics, family values, and cultural priorities. The widespread adoption of Daoist practices is a defining characteristic that sets the Yao apart from other upland peoples in Southern China.

By the 10th century, Yao tribes in the Hunan region began migrating further into Southern China, with some groups moving into provinces such as Guangdong and Guangxi, and others into Guizhou and Yunnan. Over the centuries, Mien subgroups migrated into Southeast Asia, first to Vietnam and later to Laos and Thailand. In Laos, the Mien were integrated into the French Indochinese administrative network, but following the French withdrawal in the 1950s, the United States assumed a dominant role in the region.

The Vietnam War (1956–1975) and the Secret War in Laos (1964–1973) drew the Mien into the Cold War conflict. Under CIA guidance, the Mien, along with other hill tribes like the Hmong (Miao), were recruited to combat communist forces in northern Laos. The Mien, led by two brothers Chao Mai and Chao La, primarily engaged in village defense and espionage activities near the Chinese border, though they also participated in direct combat, such as the 1970 battle at Longcheng. With the communist takeover of Laos in 1975, many Mien were forced to flee to Thailand, where they lived as stateless refugees for nearly a decade. In the late 1970s and through the early 1990s, thousands of Mien families, assisted by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), resettled in Western nations, with the majority choosing the United States, particularly in California, Oregon, and Washington. Today, the Mien-American population is estimated at approximately 75,000.

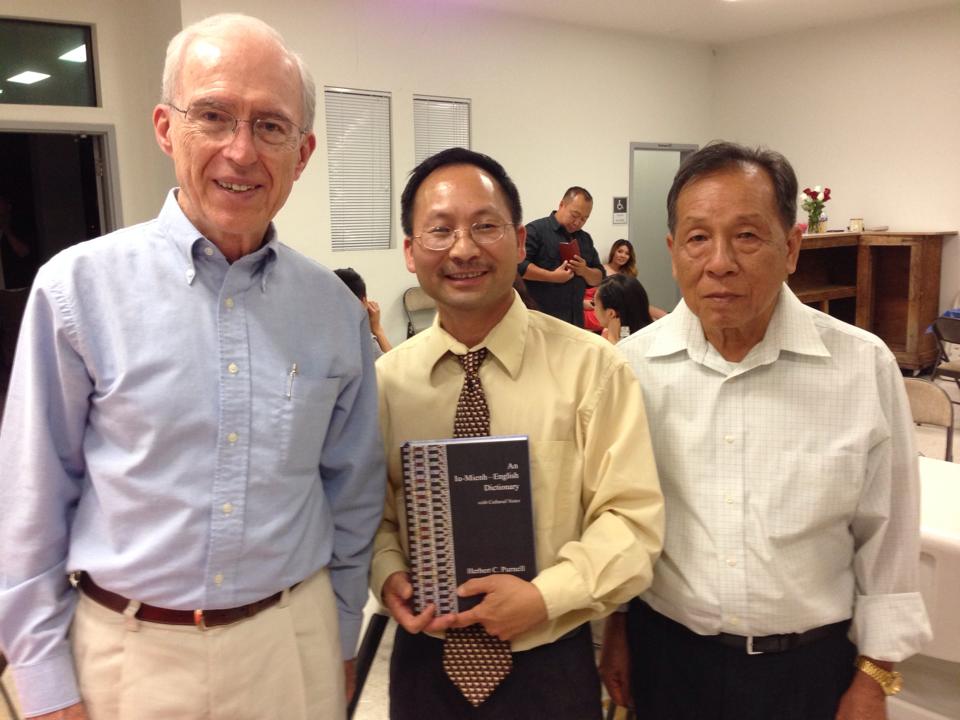

In 1984, a Yao writing system based on the Latin alphabet was developed by the Guangxi Nationality Institute and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Efforts to create a Romanized script had begun as early as the 1930s. A one-day literacy conference in Ruyan County, Guangdong (China), brought together representatives from China, the United States, and Thailand to agree on a unified script. Dr. Herbert C. Purnell, a linguist who had lived in a Mien village in Thailand, played a key role in this effort. According to Lee Romney’s article “Saving a language, and a culture,” Purnell remarked, “We gave up stuff and they gave up stuff. It meant the Mien in China, in the U.S., in France, in Canada could all use the same orthography.” Today, this script is used in the United States and parts of Southern China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.